Mind & Logic

Welcome to Mind & Logic

Ever wonder how your brain tricks you into believing you're right, even when you're wrong? Or why some arguments just seem to “click,” while others fall apart? In the **Mind & Logic** section, we’ll explore the fascinating ways our minds work in debates, arguments, and everyday thinking. Ready to challenge your assumptions?

Let’s dive into the world of logic, cognitive biases, and critical thinking!

Ready to put your thinking to the test?

What do you want to explore first?

Mind & Logic – Introduction

The Mind & Logic section is focused on understanding the mental frameworks that guide reasoning, decision-making, and critical thinking. It explores the role of logical principles in constructing sound arguments, as well as the common cognitive biases and fallacies that can lead to flawed reasoning. This section also looks at psychological tactics often used in debates or discussions to manipulate perceptions or opinions, and how to recognize and counteract them.

By mastering the concepts in this section, individuals will be able to identify faulty reasoning in their own thought processes and those of others, ensuring that arguments are based on solid logic and clear thinking. The goal is not just to win debates but to foster deeper understanding and intellectual honesty in all forms of discussion.

1. Logical Fallacies

Key Concepts:

Fallacies: Errors in reasoning that weaken an argument.

Formal vs. Informal Fallacies: Differences between flawed logic in structure (formal) vs. errors in content or context (informal).

Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning that undermine the logic of an argument. They can be formal, meaning that the flaw is in the structure of the argument, or informal, meaning the flaw lies in the content, context, or assumptions. Fallacies are often used—intentionally or unintentionally—in debates to mislead or distract from the real issue at hand. Recognizing and addressing fallacies is crucial for maintaining clear and logical reasoning.

Here are some of the most common logical fallacies:

Ad Hominem:

Definition: Attacking the person making the argument instead of addressing the argument itself.

Example: "You can’t trust what he says about climate change—he’s not even a scientist!"

Why it’s a Fallacy: The person’s background may not invalidate the argument. Focus should remain on the quality of the argument itself.

Straw Man:

Definition: Misrepresenting an opponent’s argument to make it easier to attack.

Example: "So, you’re saying we should just let criminals roam free if we don’t build more prisons?"

Why it’s a Fallacy: The argument presented is a distorted version of the opponent’s actual position, making it easier to refute.

Slippery Slope:

Definition: Arguing that a small step will inevitably lead to a chain of catastrophic events.

Example: "If we allow same-sex marriage, it’s only a matter of time before people are allowed to marry their pets."

Why it’s a Fallacy: It assumes without evidence that one event will lead to an extreme and unlikely outcome.

False Dilemma (False Choice):

Definition: Presenting two options as if they are the only possibilities, when others exist.

Example: "Either we cut taxes, or the economy will collapse."

Why it’s a Fallacy: It oversimplifies the issue by ignoring other potential solutions or outcomes.

Appeal to Authority:

is a logical fallacy where someone argues that something must be true simply because an authority figure believes it. This fallacy assumes that because a person or organization is seen as credible or has expertise, their statements or views should be accepted without question.

A person might say, "Dr. Thompson, a world-renowned scientist, believes that this diet is the best, so it must be the healthiest option." While Dr. Thompson's expertise in science might be important, the argument assumes the diet is correct solely because of the authority figure's opinion, without considering the actual evidence behind the claim.

Definition: Claiming that something must be true because an authority figure believes it.

Example: "This treatment must be effective—Dr. Smith recommends it, and he’s a world-renowned expert."

Why it’s a Fallacy: An authority figure’s endorsement does not automatically mean an argument is valid. It must be supported by evidence and reasoning.

Understanding these and other logical fallacies helps in identifying flawed arguments and maintaining logical rigor in discussions. Fallacies may be used unintentionally or as deliberate tactics to distract, mislead, or deceive.

2. Cognitive Biases

Key Concepts:

Biases: Systematic errors in thinking that affect decision-making and judgment.

Heuristics: Mental shortcuts that can lead to biased or flawed thinking.

Cognitive biases are mental shortcuts or tendencies that skew our thinking in irrational ways. These biases often lead to poor decision-making or flawed reasoning because they distort the way we process information. While cognitive biases can be useful in everyday life for making quick decisions, they often lead to errors in judgment during complex debates or discussions.

Some common cognitive biases include:

Confirmation Bias:

Definition: The tendency to favor information that confirms pre-existing beliefs and to ignore or downplay contradictory evidence.

Example: A person who believes in a conspiracy theory might only seek out articles or sources that support their view, dismissing evidence to the contrary.

Impact in Debate: Confirmation bias limits open-mindedness and makes it difficult to critically evaluate an argument from an opposing perspective.

Anchoring Bias:

Definition: The tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information encountered (the “anchor”) when making decisions.

Example: In negotiations, the first price suggested tends to become the baseline for subsequent discussions, even if it is unreasonable.

Impact in Debate: Anchoring can skew perception and judgment, making it hard to adjust to new information or arguments.

Availability Heuristic:

Definition: Overestimating the likelihood of events based on how easily examples come to mind.

Example: After hearing about a plane crash on the news, people might overestimate the risk of flying, even though air travel is statistically very safe.

Impact in Debate: The availability heuristic can cause exaggeration of risks or trends, making arguments seem more urgent or dangerous than they are.

Groupthink:

Definition: The tendency for people in groups to conform to group decisions or opinions, even when they personally disagree, to maintain harmony.

Example: In a committee, members may avoid voicing dissenting opinions to prevent conflict, leading to poor decision-making.

Impact in Debate: Groupthink stifles critical thinking and leads to poor, often unchallenged, decision-making within groups.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias where people with low ability, knowledge, or expertise in a particular domain overestimate their competence. Conversely, highly skilled individuals tend to underestimate their competence, often assuming that tasks that are easy for them are easy for others as well.

Example of Both Sides:

Overestimation (Low Ability): A person with minimal experience in public speaking may feel confident that they can deliver a flawless presentation, not recognizing the many nuances of effective communication. Their lack of self-awareness leads to overconfidence.

Underestimation (High Ability): A skilled mathematician may doubt their ability to solve a complex problem, assuming that because they found it easy, others must find it easy too. This humility can sometimes lead them to underplay their true expertise.

The effect highlights how confidence and competence are not always aligned.

Dunning-Kruger Effect:

Definition: A cognitive bias where people with low ability in a particular area overestimate their competence, while those with high ability underestimate their competence.

Example: Someone with little knowledge of economics might be overly confident in their opinions about economic policy.

Impact in Debate: This bias can lead to overconfidence in arguments that are poorly founded, while undervaluing the opinions of true experts.

Recognizing and mitigating cognitive biases is essential for ensuring that arguments are based on reason rather than emotion or flawed judgment. By understanding these biases, individuals can improve their critical thinking skills and engage in more rational, balanced debates.

3. Psychological Tactics in Debates

Key Concepts:

Manipulation: The use of psychological tactics to influence an audience unfairly.

Emotional Appeals: Triggering emotional responses to sway opinions.

Gaslighting: Causing someone to question their reality or memory.

In addition to logical fallacies and cognitive biases, debates often involve psychological tactics that are designed to manipulate or influence the audience in subtle (or overt) ways. These tactics can be very powerful, particularly when used in political or emotionally charged debates, and they often go unnoticed if the audience is not trained to recognize them.

Here are some common psychological tactics used in debates:

Appeal to Fear:

Definition: Using fear to manipulate an audience into agreeing with a conclusion, even if the fear is exaggerated or unfounded.

Example: "If we don’t pass this law, our country will descend into chaos."

Why It Works: Fear is a strong motivator, and appealing to it can override logical reasoning, especially if the threat seems urgent or personal.

Gaslighting:

Definition: A form of manipulation where someone makes another person question their reality, memory, or perceptions.

Example: "You’re overreacting. I never said that, and you know it."

Why It Works: Gaslighting creates doubt and confusion, making the victim feel uncertain about their position or even their sanity, which can undermine their ability to argue effectively.

Guilt Tripping:

Definition: Using guilt to pressure someone into agreeing with an argument or viewpoint.

Example: "If you really cared about your family, you’d vote for this policy."

Why It Works: People naturally want to avoid feeling guilty, so this tactic pressures them to conform in order to alleviate their guilt.

Bandwagon Effect:

Definition: Encouraging people to adopt a belief or behavior because "everyone else is doing it."

Example: "Millions of people support this candidate, so you should too."

Why It Works: Humans are social creatures, and the desire to conform or fit in can overpower logic or evidence-based reasoning.

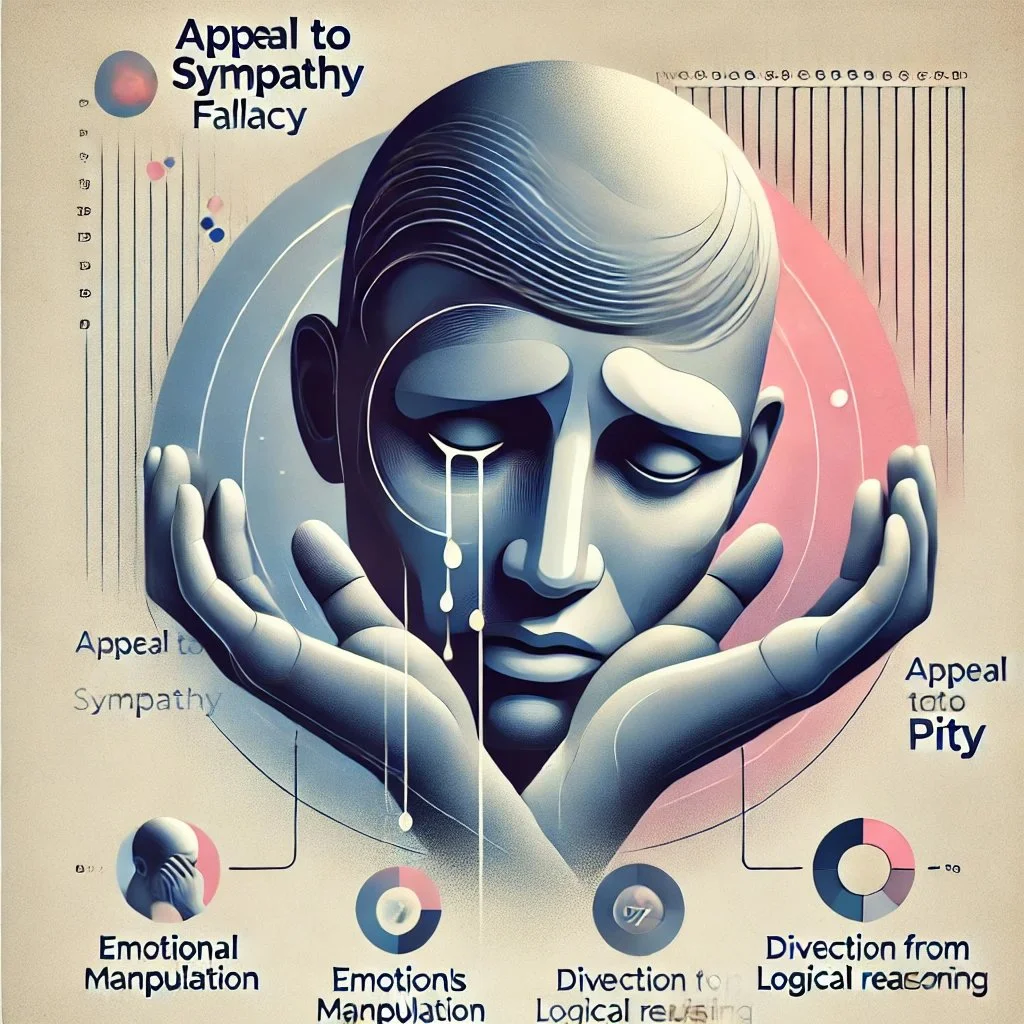

Appeal to Sympathy (or Pity):

Definition: Trying to win an argument by making the audience feel sorry for someone involved.

Example: "How can you argue against this when people are suffering so much?"

Why It Works: Emotional appeals like sympathy can cloud the audience’s ability to assess an argument objectively.

Recognizing and resisting these psychological tactics helps maintain clarity and rationality in debates. By understanding how these tactics manipulate emotions and perceptions, debaters can stay focused on the substance of the arguments rather than being swayed by underhanded techniques.

4. Logical Structures and Critical Thinking

Key Concepts:

Syllogisms: Logical structures consisting of a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion.

Conditional Reasoning: If-then logic that connects premises to conclusions.

Reductio ad Absurdum: Reducing an argument to absurdity to show its flaws.

To build sound arguments, it’s essential to understand the logical structures that underlie strong reasoning. Logical structures allow for systematic thinking, where conclusions are drawn in a step-by-step manner based on reliable premises.

Syllogism:

Description: A logical structure that uses two premises to arrive at a conclusion.

Example:

Premise 1: All humans are mortal.

Premise 2: Socrates is a human.

Conclusion: Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

Use: Syllogisms are fundamental tools for making clear, logical arguments. If the premises are true, the conclusion must logically follow.

Conditional Reasoning:

Description: Reasoning that connects an action or condition to its outcome (if A, then B).

Example: "If it rains, the ground will be wet."

Use: Conditional reasoning helps connect cause and effect in a clear and testable way.

Reductio ad Absurdum:

Description: A technique where an argument is taken to its extreme, often absurd conclusion, to show its flaws.

Example: "If we banned all cars to reduce pollution, no one could get to work or school."

Use: This technique can highlight the flaws in an argument by showing that it leads to impractical or illogical conclusions when followed to its extreme.

These logical structures are key to maintaining clarity and consistency in reasoning. By ensuring that arguments follow a logical structure, debaters can avoid ambiguity and demonstrate the soundness of their conclusions.

1. Appeal to Authority and Its Variations

Quote: "People love appeal to authority, but they don’t recognize that appeal to authority has like 30 different subsets."

Analysis: This highlights the complexity of the appeal to authority fallacy, emphasizing that there are multiple forms of this fallacy. The speaker encourages deeper understanding rather than surface-level recognition of logical fallacies. This also reflects a critique of over-simplified logical analysis, where people may call out fallacies incorrectly.

2. Cherry-Picking Data

Quote: "When you zoom out to macro scales of time, you’ll see the cycles, and it’s in a natural cycle."

Analysis: This is an example of cherry-picking, where the speaker focuses on specific data that supports their argument (natural climate cycles) while ignoring broader scientific consensus that shows the unprecedented speed of recent climate changes. This selective use of evidence distorts the overall argument.

3. Slippery Slope Fallacy

Quote: "If we allow this kind of immigration policy, we’ll see a complete collapse of our national identity."

Analysis: This is a classic example of a slippery slope fallacy, where the speaker suggests that a policy change (immigration reform) will lead to extreme, disastrous consequences (collapse of national identity), without sufficient evidence to support the inevitability of this progression.

4. False Cause

Quote: "Immigrants take jobs from citizens... They increase unemployment rates."

Analysis: This argument falls under the false cause fallacy, where the speaker incorrectly assumes that immigration directly causes unemployment among citizens. The fallacy lies in attributing unemployment to a single cause without considering other economic factors.

Future Topics for Mind & Logic

This section can expand to include:

Advanced Logic: Deeper exploration of symbolic logic and formal systems.

Critical Thinking Exercises: Techniques to sharpen reasoning skills through puzzles, paradoxes, and problem-solving.

The Psychology of Decision-Making: How the mind processes information in high-stakes debates, including the role of intuition vs. logic.

This Mind & Logic section offers a comprehensive guide to critical thinking, logical reasoning, and the cognitive processes that influence how arguments are constructed and deconstructed. By mastering these concepts, readers will be equipped to engage in rational debate and avoid common pitfalls in reasoning. Let me know if you'd like further details or additional topics!

How well did your mind hold up? Test your logic!

So, you’ve learned a lot about **fallacies**, **biases**, and how the brain loves shortcuts. But how sharp is your reasoning right now? Let’s put your mind to the test and see if you’re ready for the next level!

How would you like to challenge yourself next?

Reflection: What did you learn?

Take a moment to reflect: Do you feel more confident spotting **logical fallacies** or **cognitive biases**? Think about how you can use these skills in your next debate or decision-making process.

Want to take your learning further? Choose one of the options below to continue sharpening your reasoning: